Local Nations

Language Groups

Victorian Aboriginal Corporation for Languages (VACL) identifies 38 languages and 11 language families for Traditional Owners in Victoria as seen here. Many of the 38 languages are further divided according to family groups/clans and their traditional lands, while the 11 language families are grouped according to shared words, grammar and sounds.

This list is not definitive, as there are many contested areas of language groups and land. Whether languages are also considered “dialects” of other languages or not is also contested based on different research and definitions.

Clans are typically connected by a related language and through cultural and mutual interests, totems, trading initiatives and marriage ties. The use of the term 'clans' can be contentious, with some Trditional Owner groups identifying with the term while others favour alternative terminology, like mob or tribe (ask if you are unsure).

Prior to colonisation there were approximately 250 Indigenous languages spoken in Australia (approximately 40 in Victoria). The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) have created a map showing traditional languages across Australia. The map can be found here.

The above interactive map depicts traditional languages and is historical as many languages have dissipated and not all First Nations are defined by their language today.

Acheiving Land Justice for Traditional Owners in Victoria

Native Title Claims in Victoria

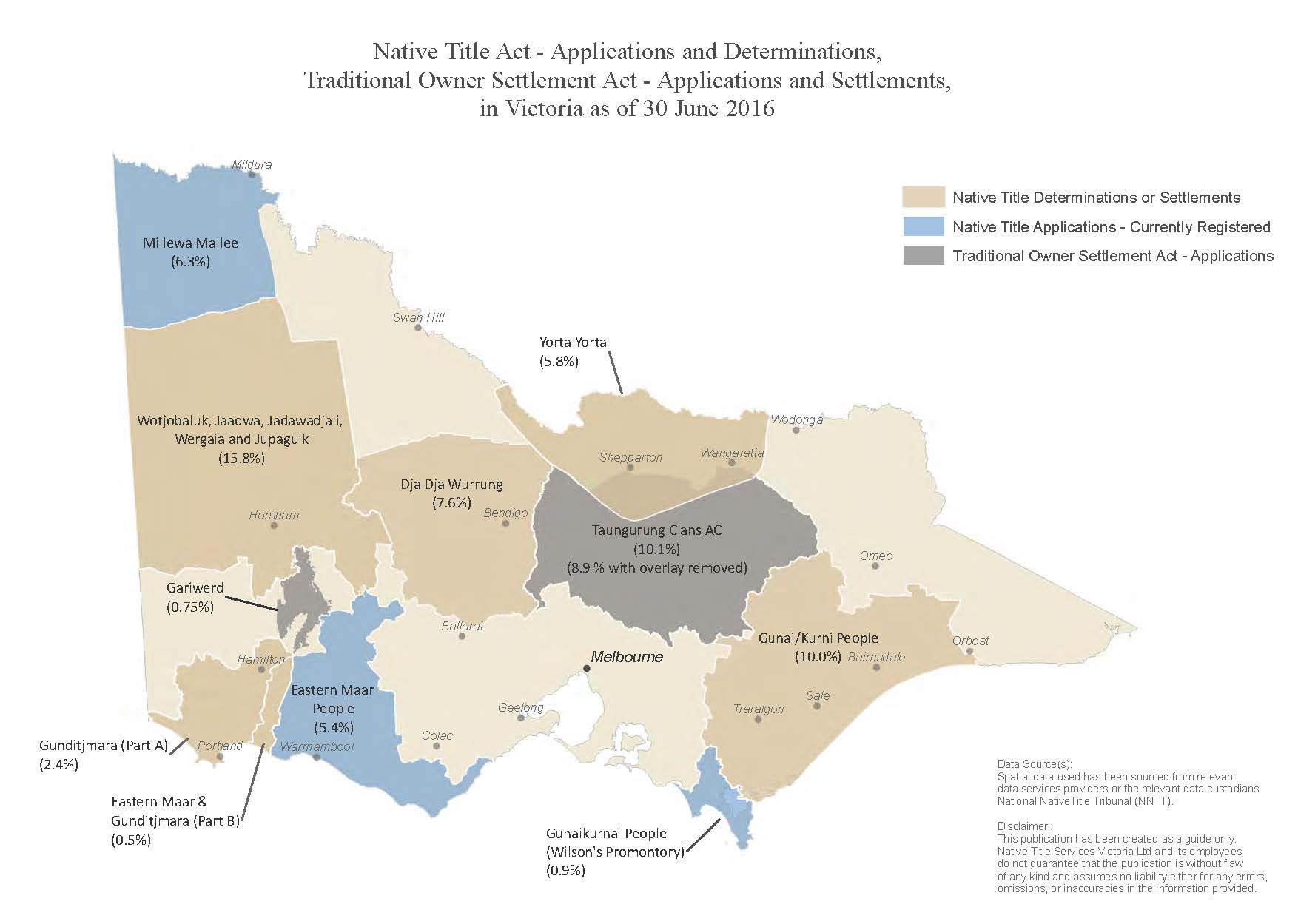

*Map of native title and Traditional Owner Settlement areas

Native title is the recognition in Australian law that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to hold rights and interests in their traditional lands and waters.

Native title was first recognised in the Australian legal system in 1992 in the historic Mabo decision. The principles of this decision were then consolidated in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). Native title can exist where traditional connection to land and waters has been maintained and where previous activity by Government has not removed it.Native title cannot take away anyone else’s valid rights and where native title rights and other rights are in conflict, the rights of the other person will always prevail.

Native title can only exist in areas of Crown land including:

· Vacant Crown land

· Some national parks, forests and public reserves

· Some types of pastoral leases

· Beaches, oceans, seas, reefs, lakes, rivers, creeks, swamps and other waters that are not privately owned.

Aboriginal groups claiming native title need to provide evidence about their identity (which might include genealogies), traditional language, connection and responsibilities to country, social and cultural system (law and custom which is acknowledged and observed), their rights and interests in land and water, and the relationship between the rights and interests and their law and custom.

Victoria currently has five determinations of native title which cover much of the state. These are the Yorta Yorta peoples, the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk peoples of the Wimmera, the Gunditjmara Peoples, the Gunaikurnai people and the Gunditjmaraand Eastern Maar peoples.

See also:

National Native Title Tribunal

Summary of the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic) (Settlement Act)

The Settlement Act was the product of close consultation between the Victorian Government, the Victorian Traditional Owners Land Justice Group and Native Title Services Victoria. It provides an alternative process for resolving native title applications to that in the Native Title Act.

The Settlement Act allows the Victorian Government to negotiate an out-of-court settlement to recognise Traditional Owners and the rights they might hold in relation to Crown land. If Traditional Owners wish to take advantage of the opportunities available under the Settlement Act, Traditional Owners must agree to withdraw any native title application and not to make any new applications.

Before the State will make a settlement agreement with a group, it must meet the definition of ‘Traditional Owner Group’ under the Settlement Act.

‘Traditional Owner Group’ is defined to include any native title holders and any persons who are recognised by the Attorney-General as the traditional owners of the land, based on Aboriginal traditional and cultural associations with the land.

The Settlement Act applies in respect of ‘public land’, including Crown land, reserves, national parks, State forests, etc.

Traditional Owners applying for a native title settlement under the Settlement Act must prepare a Threshold Statement setting out why they should be recognised as a Traditional Owner Group, and over which area of land they assert their rights, which is then evaluated by the State Government. Once the Threshold Statement is accepted, the State and the Traditional Owner Group can start negotiating a Settlement Package that meets the State’s requirements and the aspirations of the particular Traditional Owner Group.

The elements of a Settlement Package might include:

a Recognition and Settlement Agreement to recognise a Traditional Owner Group and certain Traditional Owner rights over Crown land

a Land Agreement which provides for grants of land:

for cultural or economic purposes as freehold; or

over park and reserve land as Aboriginal title to be jointly managed with the State

a Traditional Owner Land Management Agreement which provides for the joint management of national parks and reserves

a Land Use Activity Agreement which allows Traditional Ownersto comment on or consent to certain activities on public land and includes the payment of compensation for some activities

a Funding Agreement to enable Traditional Ownersto manage their obligations and undertake economic development activities;

a Natural Resource Agreementto recognise Traditional Owners’ rights to take and use specific natural resources and provide input into the management of land and natural resources

See also:

Timeline of Native Title in Victoria

1994: The first native title claim in Victoria was made by the Yorta Yorta people to land and waters covering 2,000 square kilometres along and around the Murray and Goulburn Rivers. It was one of the first native title claims in Australia following the Mabo decision in 1992.

1995: the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk peoples' native title claim was filed.

1996: Between 1996 and 1999, six applications for native title rights were lodged with the Federal Court by Gunditjamara people of south west Victoria, culminating in the ''Gunditjmara #1'' application.

1998: The Federal Court of Australia ruled against the Yorta Yorta claim.

John Howard's amendments to the Native Title Act arose from the Coalition government's "10-point plan" to extinguish and restrict Native Title grants.

2002: The Yorta Yorta people’s claim was contested through the Federal Court and High Court and on 12 December 2002, the High Court handed down its decision to members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal Community v State of Victoria and Others. The result was a negative determination. The High Court appeal was dismissed by a 5/2 majority, claiming that the 'tide of history' had washed away traditional laws and customs and thereby extinguished the native title rights of the Yorta Yorta peoples.

2004: In June 2004, the Victorian Government under Steve Bracks entered into a joint management agreement with the Yorta Yorta peoples over certain public lands that formed part of their native title claim area.

2005: On 13 December 2005, native title was determined to exist for the first time in Victoria for the Wotjobaluk, Jaadwa, Jadawadjali, Wergaia and Jupagulk peoples of the Wimmera. This consent determination was significant as it was the first successful native title claim in south-eastern Australia and in Victoria. It was also historic as the ruling acknowledged that rather than the 'tide of history' washing away native title rights, " [traditional laws and customs] evolve over time in response to new or changing social and economic exigencies to which all societies adapt as their social and historical contexts change".

2006: ‘Gunditjmara #2’, the mob’s second application, was lodged over parcels of unclaimed Crown land within the boundary of the first claim.

2007: On 30 March 2007, the Gunditjmara people were also found to hold native title over the majority of almost 140,000 hectares of land, national parks, reserves, rivers, creeks and sea north-west of Warrnambool in Victoria’s western district. The Victorian Government consented to this Federal Court determination. This was Australia's 100th native title registered determination.

2010: On 23 September 2010 the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic) came into effect. It provides an alternative to the settlement framework set out in the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth).

2010:On 22 October, 2010, theGunaikurnai people were recognised as native title holders over lands in Gippsland in south east Victoria. At the same time the Gunaikurnai people signed the first agreements with the Victorian Government under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010. The agreement area extends from west Gippsland near Warragul, east to the Snowy River and north to the Great Dividing Range. It also includes 200m of sea country offshore.

2011: The Victorian Government and the Gunaikurnai People signed a Participation Agreement in 2011, providing for the payment of a lump sum into the Victorian Traditional Owners Trust.The Trust forms an important part of the settlement process as it provides an independent, secure and cost-effective option for the management of settlement funds.

On 27 July 2011, the Federal Court found that the Gunditjmara and Eastern Maar peoples hold native title over some areas of Crown land in the south west of Victoria. The determination area is an area roughly between the Shaw and Eumeralla Rivers and includes Deen Maar (or Lady Julia Percy Island) which is of particular cultural significance to the Gunditjmara and Eastern Maar Peoples. The area has been referred to as ‘Part B’ because it resolved the second part of two Native Title claims first made by the Gunditjmara in 1996.

2013: On 28 March 2013, the State and the DjaDjaWurrung people entered into a Recognition and Settlement Agreement under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act. It was the culmination of 18 months of negotiations between the State and DjaDjaWurrung people. The agreement was the first comprehensive settlement under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010 (Vic). The agreement settles four native title claims in the Federal Court dating back to 1998.

Sourced from: First Nations Legal and Research Services

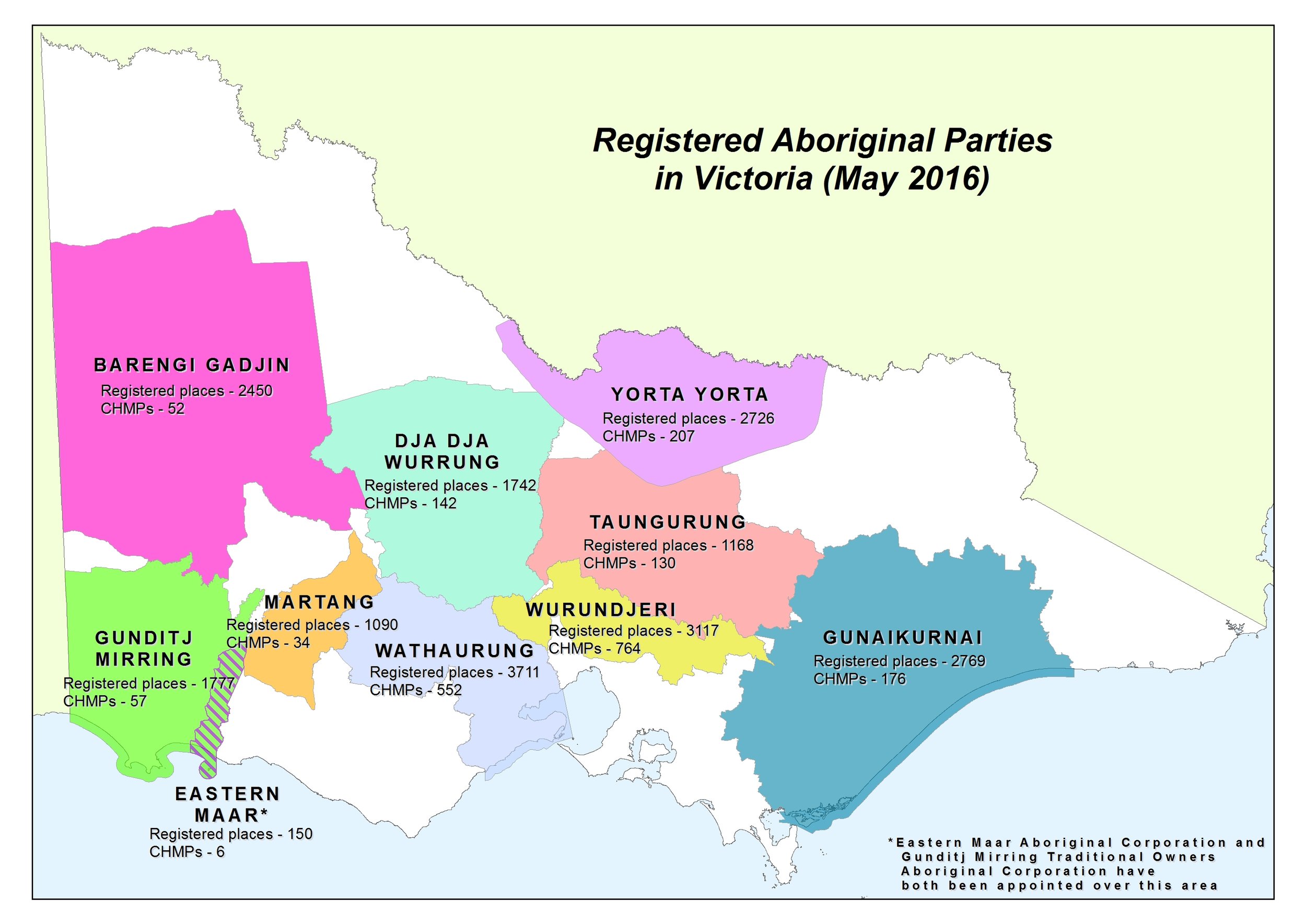

REGISTERED ABORIGINAL PARTIES

Registered Aboriginal Parties (RAPs) are organisations that hold decision-making responsibilities under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 (Vic) for managing and protecting Aboriginal cultural heritage in a specified geographical area. RAPs are appointed by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council.

There are currently 11 RAPs in Victoria. These RAPs currently cover approximately 60% of Victoria. This structure of governance has given Traditional Owner communities control over their lands and communities, yet they only represent the legally recognised lands of the Traditional Owner groups which may not reflect traditional borders. See where these RAPs lie and what they have accomplished below.